I want to destroy ownership in order that possession and enjoyment may be raised to the highest point in every section of the community.

George Bernard Shaw

Over the years there has been a considerable amount of time and energy spent on discussing social enterprise – what it is, what it could be, what impact it has. At times this has been quite a creative and stimulating experience, while at other times it has been negative and tiresome.

In all these discussions, I believe, not enough emphasis has been laid on ownership. Who owns these social enterprises and are they accountable not only to themselves but also to the wider public? Accountability is going to become more and more important for social enterprises as they take on public and community sector contracts and have to account for their actions to a variety of different stakeholders.

With private corporations, ownership is often a slippery beast. The ownership of the ‘means of production’ can be difficult to determine as it is, at times, not fully declared – but is often the key to understanding why an organisation acts in the way it does.

Andy Wightman in his recent research and writings illustrates this in the following paragraph which refers to land specifically, but also can be extended to property and the ‘means of production’:

Land is about power. It is about how power is derived, defined, distributed and exercised. It always has been and it still is thanks to a legal system that has historically been constructed and adapted to protect the interests of private property. ‘The Poor Had No Lawyers’ by Andy Wightman

Guy Shrubsole in his recent book, Who Owns England, writes that less than one per cent of the population owns about half of England and Wales. This cannot be right if we are trying to create a fairer more equal society.

Faced with these glaring inequalities, perhaps the only way to fully understand them is to go back into history and trace the threads that lead us to where we are now. Thus, indulge my historical and simplistic foraging…

Before capitalism, there was a feudal system in the UK where a reigning monarch could grant whole tracts of land along with a title as a reward to the aristocracy for some form of favour. This ownership of land meant money could be made and inequality could persist – land being the primary source of wealth.

At the time of the British Empire, European imperialists conquered foreign lands and introduced a form of ownership applying European laws – in effect taking control of whole areas through the ownership of land. As an aside, many tribes in Africa could not get their heads around the ownership of land as it was a concept that challenged their existing value system – land to grow crops, air to breathe, panoramic beauty where all things that existed for all the people and, prior to colonisation, could not be owned in our sense of the word.

In Victorian times ownership and property became all-important causing increased social and economic inequality as ownership of property would be passed on within families. In fact, those not owning property were excluded from voting, which reinforces Wightman’s comments cited above.

In the mid-19th century, the co-operative movement emerged as a way that goods and services could be produced for the benefit of the workers and the wider community, not just the factory owners. Workers co-operatives were created so that they themselves owned the means of production.

In the last two centuries, many voluntary organisations and charities adopted a form of ‘trust’ where ownership was not held by an individual or indeed a group of people. Rather, those organisations were run and managed by ‘stewards’ operating in the best interests of the organisation to provide maximum benefit to beneficiaries. A similar structure was adopted by many housing associations.

In the 1970s, Community Co-operatives were established in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland responding to negative economic factors – such as depopulation, dwindling services and a lack of employment opportunities. This model was largely copied by Community Businesses – functioning business enterprises that were owned and controlled by local people for the benefit of those living in local communities. In these cases, ownership of the business was held by the ‘community’ and not by individuals.

This now brings us to the current situation with social enterprises. They are not public sector organisations, nor are they part of the private sector where individuals own organisations or companies. Social enterprises sit somewhere between these two much larger sectors – and this, I would argue, is why ownership of a social enterprise is key to our overall understanding of what is and what is not a social enterprise.

Yvon Poirier, a French-Canadian pioneer within the social economy, explains the origins of the term ‘social enterprise’ stating that its meaning originally…

…relates exclusively to the type of ownership. By ‘social’, one means that the ownership is by humans (persons) and not by shareholders

Social Economy and Related Concepts Paper, 2012

He then goes on to explain that in the 1990s the term ‘social enterprise’ – particularly in the English-speaking world, took on a totally different meaning. The term ‘social’ in recent times has come to mean the purpose or sector of activity and not the ownership of the enterprise.

This shift in meaning is significant as the end result of social enterprise activity has become more important than the type of organisation they are. This has led to current thinking which stresses the dominance of social impact over how that impact is delivered and crucially linked to this, the ownership of the organisation.

In trying to understand the creation and evolution of social enterprise, we have become too bogged down in what a social enterprise does and what impact it claims. We are guilty of overlooking the issue of ownership and this is a situation I feel needs addressing.

In response to the ownership of a social enterprise, some activists have stressed the need for an ‘asset lock’. This ensures that individuals do not, and will not, benefit directly from their involvement in the enterprise. In a way, this skirts around the central issue which is about who owns the enterprise – indeed, who owns and thus controls, the means of production. Ownership, in my view, should be more central to our understanding.

Many organisations that claim to be social enterprises are up-front about their social impact credentials, hoping that no-one will look too closely at the ownership of their enterprise. Of course, those private sector businesses with strong Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) statements should be applauded – particularly if they genuinely report on what social benefits they provide and do not only use it as a marketing tool.

However, praising these private businesses for their CSR reporting does not qualify them as a ‘social enterprise’. In my view, a social or community enterprise is about collective ownership maximising benefit to a wider society.

When thinking about social enterprises, the first questions to ask are, who owns it and what is the ownership structure. This will help in understanding where that organisation is coming from and why it is acting in that particular way. The key issue around ownership is whether or not the social enterprise is acting in a way that maximises social or community benefit, or is acting solely in the interest of the owners.

Collective ownership operating on behalf of a wider community ensuring future sustainability to benefit society has to be preferred to privately owned businesses masquerading as social enterprises.

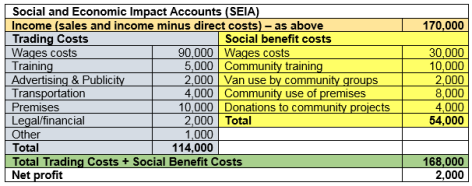

In fact, I would go further. I believe that all organisations that have a central social or community purpose should keep regular and transparent social accounts. These ‘accounts’ should affirm the key things about the organisation, including ownership, and at the same time provide an indication of the social and community impact backed up by evidence.

And going even further, I believe that in order to give social reports integrity, they should be subject to an independent audit. For information on a practical way forward, see www.socialauditnetwork.org.

You will have noticed the George Bernard Shaw quote at the start of this blog. He used the word ‘destroy’ which indicates fairly drastic action. What he is arguing for is the destruction of ‘private ownership’ as opposed to ‘collective’ or ‘communal ownership’ so that owning things and living contented lives is not in the hands of the few for their own purposes but is shared by the many for everyone’s benefit.

Alan Kay, April 2019

Alan was one of the original founders of the Social Audit Network (SAN) which encourages social and community organisations to keep regular social accounts and have them independently audited – www.socialauditnetwork.org.

Alan is retired but during his working life, he had more than 35 years of experience in community development and social enterprise sector in the UK and overseas. Alan’s background was in overseas development. Since returning to Scotland in 1988 he mainly worked with community-owned enterprises and social enterprises. He remains loosely attached to Glasgow Caledonian University as a Senior Visiting Fellow of the Yunus Centre for Social Business and Health.

Email: alan.kay20@gmail.com or alan.kay@gcu.ac.uk